Grover

Cleveland "Pete" Alexander (1887 - 1950) was one of baseball's most

tortured individuals. He was named after the sitting US president

because his parents had aspirations that he would study law, but young

Grover was more into baseball. He played in various minor league teams

and was doing well when he was hit in the head by an errant throw. He

developed double vision that lasted for months and

epilepsy that would plague him for the rest of his life. But he pitched

well between seizures and ended up with the Philadelphia Phillies,

where he made an immediate impact, winning 28 games. He excelled for

Philadelphia, winning 30 games in three consecutive seasons, but they

traded him to the Cubs knowing he'd be drafted. He was indeed drafted

and was shipped to the Western Front, where he lost part of his hearing

from the artillery fire and came back with a strong case of PTSD. The

anxiety and the epilepsy led him to embrace alcohol, and he would spend

the rest of his life an alcoholic. Yet he was still in command on the

mound. He pitched well with Chicago, including a 12-inning complete game

on September 20, 1924 for his 300th win. The Cubs sold him to the

Cardinals in 1926, with whom he would have his most famous baseball

moment. Coming in as a reliever with the bases loaded in Game 7 of the

World Series against the Yankees, he struck out super-rookie Tony

Lazzeri, then shut out the Yankees to save the game that ended when Babe

Ruth was thrown out trying to steal second. He would have a few more

good years with the Cardinals before returning to the Phillies for one

last season in 1930. He would retire with 373 wins, third all time, and

90 shutouts, which is second all time.

Without baseball to

distract him, he soon fell victim to the alcoholism, PTSD, and epilepsy

that was plaguing him. He could never hold onto a steady job, even

working for a time at a flea circus. He separated from his wife, though

they remained close. He lived in constant poverty, and suffered from

many health ailments. He was well enough to attend the 1950 World

Series, but shortly afterward his heart gave out on him and he died on

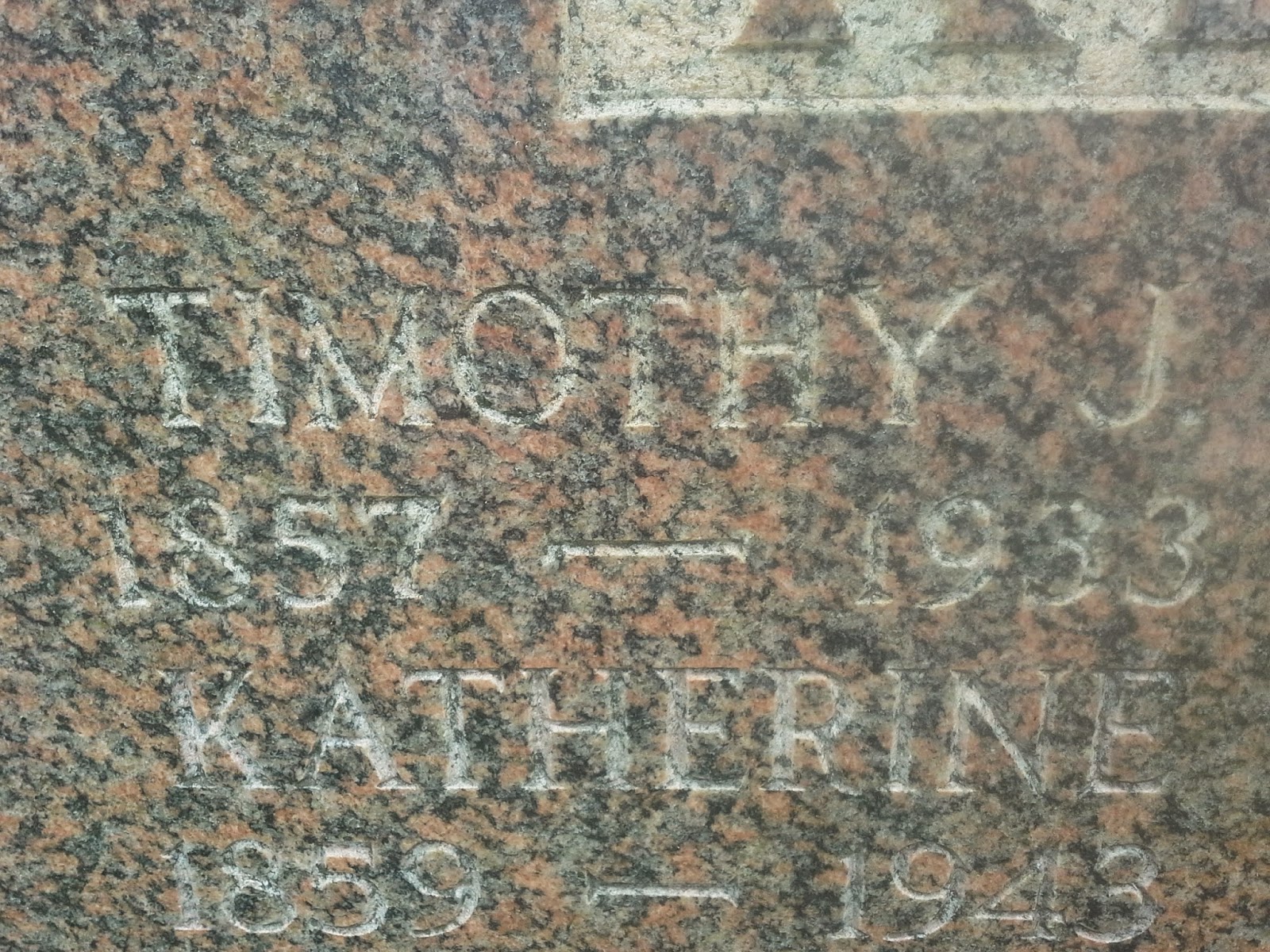

November 4, 1950. He was only 63. He was buried with military honors in

Elmwood Cemetery in St. Paul, Nebraska.

|

No comments:

Post a Comment